The Subscription Trap Was Never About Convenience

The subscription economy was sold as freedom, flexibility, and modern convenience. No long-term commitments, no bulky physical products, just instant access to everything you want. But beneath the marketing language sits a system designed to keep users permanently paying, permanently dependent, and permanently monitored. What looks like progress is actually a shift in power away from individuals and toward centralized control.

In the past, ownership meant closure. You bought something, the transaction ended, and the relationship stopped there. Subscriptions erase that ending. Every month becomes a checkpoint where access can be adjusted, restricted, or revoked. The product never truly belongs to you, and the company never truly lets go of you. That ongoing dependency is not a side effect; it is the core feature.

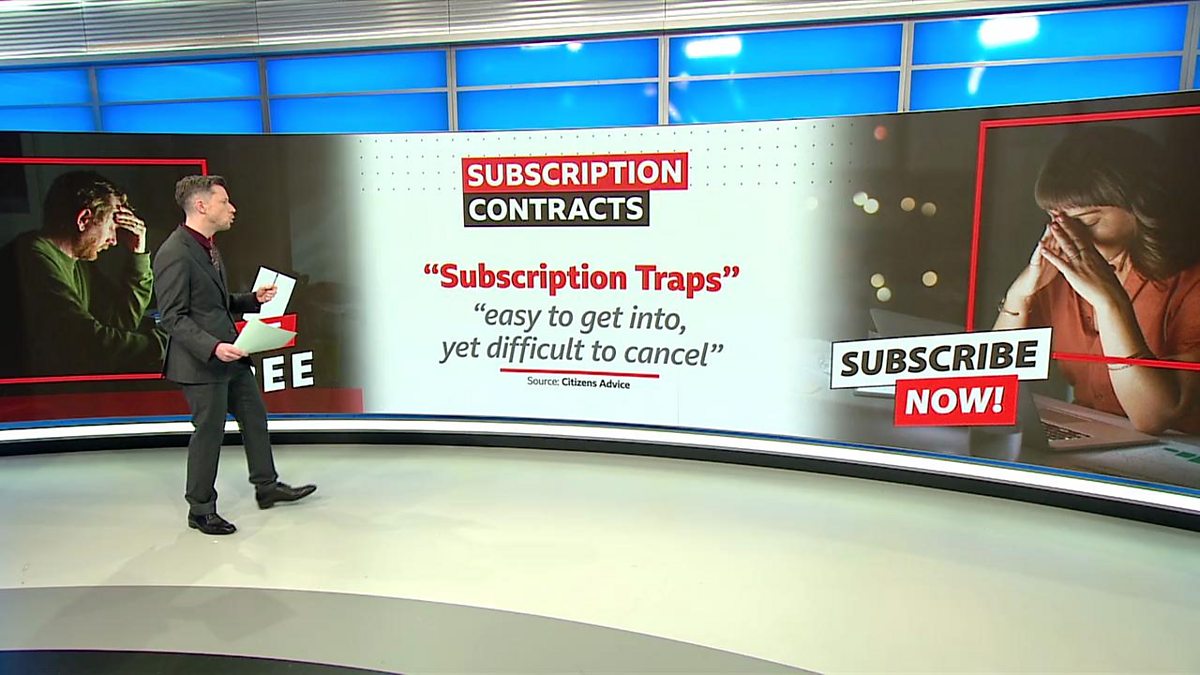

Convenience was the bait. No installations, no maintenance, no updates to worry about. Everything “just works” as long as you keep paying and following the rules. But convenience comes with conditions, and those conditions are written unilaterally. Terms of service change quietly, prices creep upward, and features disappear while users are told it’s for their benefit.

Subscriptions also normalize constant surveillance. To manage access, companies must track usage, behavior, and engagement. What you watch, how long you play, when you log in, and where you click all become data points. This data is not just used to improve services; it is monetized, analyzed, and leveraged to shape future behavior. You are not just the customer — you are part of the product.

The psychological impact is subtle but powerful. Subscriptions create a fear of loss rather than a sense of ownership. People keep paying not because they actively use the service, but because they don’t want to lose access “just in case.” This turns spending into a defensive habit instead of a deliberate choice. Over time, sunk costs replace rational evaluation.

Bundles intensify the trap. Services are packaged together so canceling one feels like losing several things at once. Games, music, movies, cloud storage, productivity tools, even car features are wrapped into monthly plans. The more integrated the bundle, the harder it becomes to leave without disrupting daily life. Exit friction is engineered intentionally.

Price increases reveal the true nature of subscriptions. Once users are locked in and alternatives feel inconvenient, prices rise. Companies justify this with vague language about “added value” or “expanded features,” even when the core experience stays the same. Users rarely have negotiating power because there is no ownership leverage to fall back on.

Subscriptions also quietly rewrite expectations around durability. Products are no longer expected to last indefinitely. Software sunsets, servers shut down, and services disappear entirely. Instead of outrage, users are conditioned to accept loss as normal. When access ends, people shrug and move on, trained not to expect permanence.

This model benefits corporations because it stabilizes revenue and concentrates power. Predictable monthly income pleases investors, while centralized control simplifies enforcement and compliance. Users become line items on a balance sheet, valued more for their retention metrics than their satisfaction. The longer someone stays subscribed, the more valuable they are — regardless of benefit received.

The real danger is cultural. When everything becomes a subscription, ownership itself begins to feel outdated. People stop expecting control, transferability, or longevity. A generation grows up believing that access is the natural state of things, and that losing it is inevitable. This mindset makes resistance harder and dependency easier to justify.

Escaping the subscription trap doesn’t mean rejecting modern technology entirely. It means recognizing the difference between tools that serve you and systems that manage you. It means choosing ownership when possible, diversifying platforms, and refusing to confuse monthly permission with real value. Awareness is the first crack in a system that depends on passive acceptance.

The subscription economy was never just about convenience. It was about control, predictability, and leverage. Once you see that clearly, the illusion breaks. What remains is a simple question every user must answer for themselves: how much of your life are you willing to rent?

Comments

No comments yet, be the first submit yours below.